Erica Green’s life took a pivotal turn seven years ago when she learned through a Facebook post that her brother had been shot. Distraught, she rushed to the hospital run by Denver Health, the city’s safety-net system, where her brother was being treated. However, Green was unable to get any information from the emergency room workers, who complained that she was causing a disturbance.

Feeling helpless and overwhelmed, she was soon approached by a familiar face from her Denver neighborhood, Jerry Morgan. Morgan, who had also rushed to the hospital after his pager alerted him to the shooting, worked as a violence prevention professional with the At-Risk Intervention and Mentoring program (AIM). His role was to support gun-violence victims and their families at the hospital, and that day, he was there for Green and her brother.

“Jerry’s presence made the traumatic experience so much more bearable. After that, I knew I wanted to do this kind of work,” Green said.

Today, Green is the program manager for AIM, a hospital-linked violence intervention initiative that was launched in 2010 as a partnership between Denver Health and the nonprofit Denver Youth Program. AIM has since expanded to include Children’s Hospital Colorado and the University of Colorado Hospital.

AIM is among dozens of hospital-linked violence intervention programs across the United States. These programs strive to identify and address the social and economic factors that contribute to someone ending up in the emergency room with gunshot wounds. These factors can range from inadequate housing and job loss to feeling unsafe in one’s neighborhood.

Programs like AIM that adopt a public health approach to countering gun violence have shown promising results. For instance, a similar program in San Francisco reported a fourfold reduction in violent injury recidivism rates over six years. However, recent executive orders by President Trump calling for the review of the Biden administration’s gun policies and trillions of dollars in federal grants and loans have raised concerns about the long-term federal funding for these programs. While some organizers believe their programs will remain unaffected, others are exploring alternative funding sources.

“We’ve been worried about, if a domino does fall, how will it impact us? There are a lot of unknowns,” said John Torres, associate director for Youth Alive, an Oakland, California-based nonprofit.

Gun violence has increasingly become a leading cause of death among children and young adults since the start of this decade. According to federal data, it was associated with more than 48,000 deaths among people of all ages in 2022. Chethan Sathya, a New York-based pediatric trauma surgeon and a National Institutes of Health-funded firearms injury prevention researcher, believes this alarming statistic underscores the importance of treating gun violence as a pressing healthcare issue. “It’s killing so many people,” Sathya said.

Studies have also shown that a violent injury significantly increases an individual’s risk of sustaining future injuries, with the risk of death escalating substantially by the third violent injury, as per a 2006 study published in The Journal of Trauma: Injury, Infection and Critical Care.

Benjamin Li, an emergency medicine physician at Denver Health and the health system’s AIM medical director, believes that the emergency room is an ideal setting to intervene in gun violence by attempting to reverse-engineer what led to a patient’s injuries.

“If you are just seeing the person, patching them up, and then sending them right back into the exact same circumstances, we know it’s going to lead to them being hurt again,” Li said. “It’s crucial we address the social determinants of health and then try to change the equation.”

This can involve offering alternative solutions to gunshot victims who might otherwise seek retaliation, explained Paris Davis, the intervention programs director for Youth Alive.

“If that’s helping them relocate out of the area, if that’s allowing them to gain housing, if that’s shifting that energy into education or job or, you know, family therapy, whatever the needs are for that particular case and individual, that is what we provide,” Davis said.

AIM outreach workers meet gunshot wound victims at their hospital bedsides to have what Morgan, AIM’s lead outreach worker, calls a tough, nonjudgmental conversation on how the patients ended up there.

Using this information, AIM helps patients access the resources they need to overcome their biggest challenges after they’re discharged. These challenges can range from returning to school or work to finding housing. AIM outreach workers might also attend court proceedings and assist with transportation to healthcare appointments.

“We try to help in whatever capacity we can, but it’s interdependent on whatever the client needs,” Morgan said.

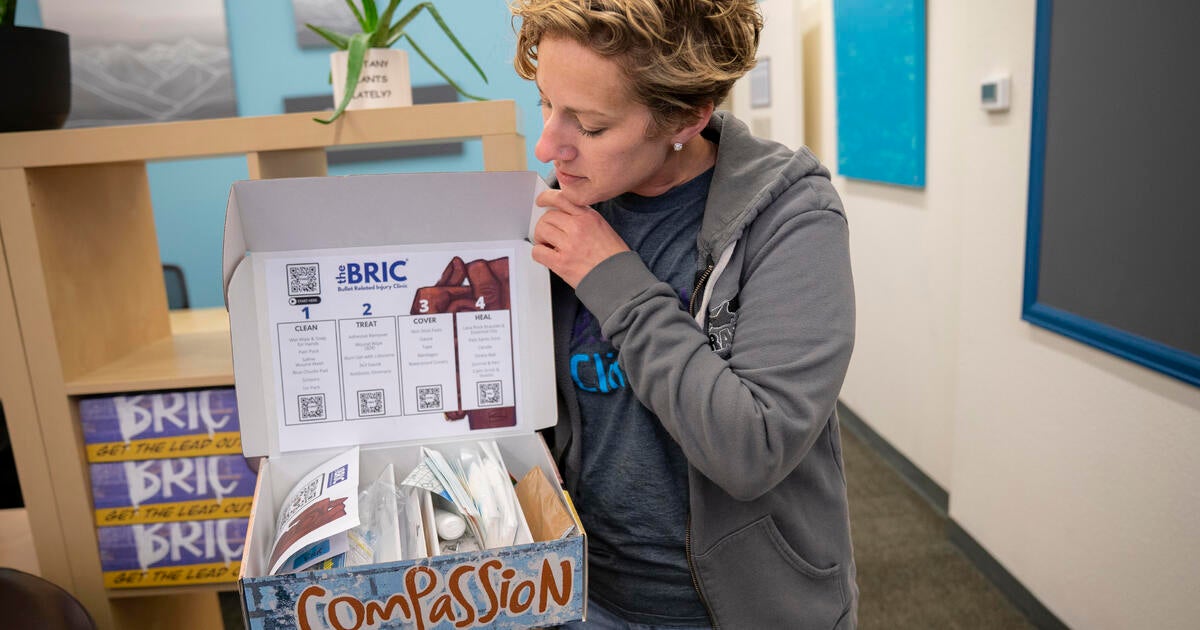

Since its inception in 2010, AIM has expanded from three full-time outreach workers to nine. This year, it opened the REACH Clinic in Denver’s Five Points neighborhood. This community-based clinic offers wound-care kits, physical therapy, and behavioral, mental, and occupational healthcare. In the coming months, it also plans to add bullet removal to its services. The REACH Clinic is part of a growing movement of community-based clinics focused on violent injuries, including the Bullet Related Injury Clinic in St. Louis.

Ginny McCarthy, an assistant professor in the Department of Surgery at the University of Colorado, described REACH as an extension of the hospital-based work, providing holistic treatment in a single location and building trust between healthcare providers and communities of color that have historically experienced racial biases in medical care.

Caught in the Crossfire, created in 1994 and run by Youth Alive in Oakland, is considered the nation’s first hospital-linked violence intervention program and has inspired many others. The Health Alliance for Violence Intervention, a national network initiated by Youth ALIVE to advance public health solutions to gun violence, counted 74 hospital-linked violence intervention programs among its membership as of January.

The alliance’s executive director, Fatimah Loren Dreier, likened medicine’s role in addressing gun violence to that of preventing an infectious disease, such as cholera. “That disease spreads if you don’t have good sanitation in places where people aggregate,” she said.

Dreier, who also serves as executive director of the Kaiser Permanente Center for Gun Violence Research and Education, said medicine identifies and tracks patterns that lead to the spread of a disease or, in this case, the spread of violence.

“That is what healthcare can do really well to shift society. When we deploy this, we get better outcomes for everybody,” Dreier said.

The alliance, of which AIM is a member, offers technical assistance and training for hospital-linked violence intervention programs and has successfully petitioned to make their services eligible for traditional insurance reimbursement.

In 2021, President Joe Biden issued an executive action that allowed states to use Medicaid for violence prevention. Several states, including California, New York, and Colorado, have passed legislation establishing a Medicaid benefit for hospital-linked violence intervention programs.

Last summer, then-U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy declared gun violence a public health crisis, and the 2022 Bipartisan Safer Communities Act earmarked $1.4 billion in funding for a wide array of violence-prevention programs through next year.

However, in early February, Mr. Trump issued an executive order instructing the U.S. attorney general to conduct a 30-day review of a number of Biden’s policies on gun violence. The White House Office of Gun Violence Prevention now appears to be defunct, and recent moves to freeze federal grants have created uncertainty among the gun-violence prevention programs that receive federal funding.

AIM receives 30% of its funding from its operating agreement with Denver’s Office of Community Violence Solutions, according to Li. The rest is from grants, including Victims of Crime Act funding, through the Department of Justice. As of mid-February, Mr. Trump’s executive orders had not affected AIM’s current funding.

Some who work with the hospital-linked violence prevention programs in Colorado are hoping a new voter-approved firearms and ammunition excise tax in the state, expected to generate about $39 million annually and support victim services, could be a new source of funding. However, the tax’s revenues aren’t expected to fully flow until 2026, and it’s not clear how that money will be allocated.

Catherine Velopulos, a trauma surgeon and public health researcher who is the AIM medical director at the University of Colorado hospital in Aurora, said any interruption in federal funding, even for a few months, would be “very difficult for us.” But Velopulos said she was reassured by the bipartisan support for the kind of work AIM does.

“People want to oversimplify the problem and just say, ‘If we get rid of guns, it’s all going to stop,’ or ‘It doesn’t matter what we do, because they’re going to get guns, anyway,'” she said. “What we really have to address is why people feel so scared that they have to arm themselves.”